March 16 2023

The video footage we see in casework is often very poor quality, bearing little resemblance to that seen in TV dramas and films. Invariably it has a low resolution, it can be dark with poor contrast, the subjects of interest are often distant from the camera and they move across the field of view. Footage from police body-worn cameras and hand-held phones can be very jerky and chaotic. The clips can be very long, with the period of interest only lasting for a few minutes or even seconds. Without the right 'Player', repeatedly moving back through a clip to review it can be difficult and frustrating.

How an Imagery Expert Witness can help

We consider 'Video Enhancement' as the process of trying to make video footage easier to view. This includes clarifying what can be seen or not seen, as well as what is occurring, all within the bounds of preserving its integrity. To do this we can:

We can also produce 'PDF' flipbooks of frames captured from short sections of enhanced footage. These allow you to move easily backwards and forwards through the video a frame at a time. Click on the links to see an example of a Questioned Video and a Flipbook.

In terms of reviewing activity, most of the footage we receive can be improved by a combination of the above actions, although the degree to which it can be improved will depend on the quality of the source material.

Enlarging footage to show small details

When images are enlarged, new pixels are created, changing the image. This process is called interpolation and occurs automatically via one of several different algorithms (e.g. Bicubic, Nearest Neighbours). Each method has different pros and cons. For example: A 'nearest neighbours' algorithm preserves hard edges but can result in a blocky image, which is particularly noticeable on diagonal and curved edges. However, the results do represent what the camera actually captured. A 'bicubic' algorithm produces smoothed edges and a more presentable image but, if the object of interest is composed of only a few pixels, it can potentially distort shapes leading to erroneous interpretations. Interpolation cannot restore information that was never there.

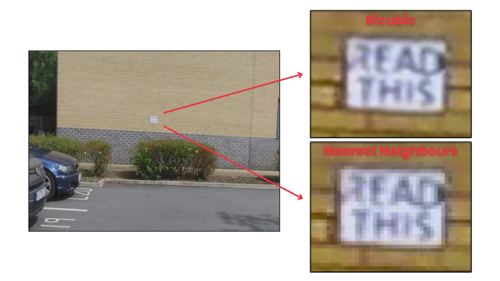

Some sort of interpolation occurs whenever an image is enlarged including 'pinch zooming' on a phone, upscaling from HD to 4K on a TV, or when displaying imagery on a larger screen (such as in Court). Figure 1 shows enlargements using these two different methods.

Figure 1: Enlargement of wall-mounted sign using two different interpolation methods (bicubic and nearest neighbours). The sign was A4 size, but only 29x22 pixels in the original image. The letters are the size of the characters on a vehicle registration plate.

Source material in theory

In all the work we do, whether a simple enhancement or an analysis leading to a comparison, we should be provided with the 'best version' of the footage available. The quality of the source material is particularly critical when small details are being analysed or compared.

So, what is the 'best version'? Guidelines approved by the National Police Chiefs’ Council’s (NPCC) lead for CCTV stipulate that:

Source material in practice

Assuming the footage was properly downloaded, this 'working copy', is the best version we can hope for. However, it is usually the case that the footage available via the digital storage platforms used by the courts, such as Egress, evidence.com etc, has been derived from the 'working copy', and can be of a lesser quality.

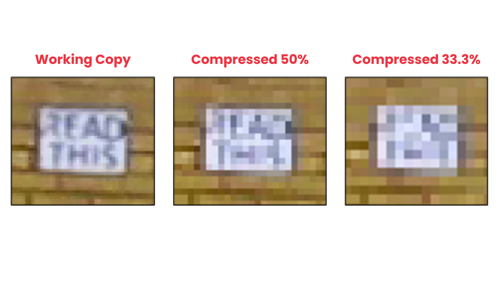

Loss of quality can occur if the footage is converted from a difficult to play format, which requires specific software ('Player') into a universal, easy to play format such as '.mp4'. It can also occur if the footage is compressed to reduce the amount of storage required. Compression, the opposite of interpolation, is done by removing pixels from an image resulting in loss of detail. Similar deteriorations can occur when different clips are stitched together to produce compilations.

Converted footage is sometimes indicated by the word 'transcode' in file names. Figure 2 illustrates this loss of detail by comparing a 'nearest neighbours' enlargement of a frame from a 'working copy' of a video clip with similar enlargements from compressed versions of this clip.

Figure 2: Nearest neighbour enlargements from a frame of video

We often encounter where CCTV footage has not been properly downloaded per best practice, or at least if it has, we are not provided with it. Alternative methods of video recovery include 'Screen Capture' and filming the footage with a body-cam (called BWV or Body Worn Video) or mobile phone as it plays on a screen. Screen capture uses dedicated software to record everything that is shown on a screen as the clip is played, including player icons and anything else on the desktop (if the clip is not maximised). Depending on the quality of the screen and the area occupied by the video, it can result in significant image degradation and even change the aspect ratio (so people/objects can appear squashed or stretched). Filming the screen is the worst of all worlds as there is often interference between the camera and the screen, reflections from the screen and the camera is rarely held still and square to the screen. A CSI would never recover a fingerprint by filming it with a body-cam, so why should video evidence be treated differently? Figure 3 compares a cropped frame from a video clip filmed as it played on a screen, with the same crop from a 'working copy' of the video.

Figure 3: Comparison of a cropped frame from a video clip a) filmed as it played on a screen and b) from a working copy. Note the letter 'A' on the yellow card is not legible in 3a.

It is accepted that directly downloading footage can be difficult and may not always be possible, but the NPCC Framework for Video Based Evidence (published July 2022) stipulates that the recording of footage playing on a screen by attending officers is only to be done as a last resort where all other options have been exhausted or where there is a present and immediate risk of harm. Authorisation for this must be obtained from the SIO and documented and a native download by more highly trained staff requested.

Review of imagery provided in casework

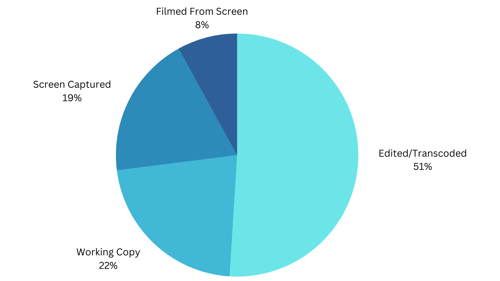

A review of our cases from August 2021 to June 2022 showed we received 'working copies' of footage in only 22% of cases. Overall, the review found the following:

Despite clear guidelines, our perception is that the recovery of video by filming it as it plays on a screen is becoming more common. For the 27% of cases where the footage had been screen captured or filmed from the screen, it may be that the footage had never been properly downloaded. However, for the 51% of cases where only edited/transcoded footage was provided, it is unclear why the 'working copies' which these had been derived from were not disclosed.

As can be seen from Figures 2 and 3, for optimal enhancement, it is vital we are provided with the best available version of any footage. Sub-optimal footage will not necessarily preclude any analysis, but it can limit the types of questions which can be answered.

If you have queries or questions about video and video enhancement, please get in touch with Nigel Cook.